Poor cancer patients in India would welcome Indian apex court’s decision, dismissing Novartis’ appeal for a patent for its anti-cancer drug, Gleevec. The Supreme Court judgement, delivered by Justice Aftab Alam and Justice Ranjana Desai, has called for a strict interpretation of section 3(d).

India’s  Cancer Patients Aid Association (CPAA) has described the ruling as a huge victory for human rights. Y. K. Sapru of CPAA says, “Our access to affordable treatment will not be possible if the medicines are patented.â€

The ruling is a landmark for the interpretation of section 3(d) of the Patents Act 1970Â which prevents patenting of new forms of already known molecules, also known as evergreening, unless the new drug offers a significant enhancement in efficacy.

The Swiss pharmaceutical company argued that better physico-chemical qualities would satisfy the test of enhanced efficacy.

Rejecting Novartis’ argument, the Supreme Court held that the physio-chemical properties of the drug may be beneficial for patients in some manner but they do not meet the standard of efficacy required by Section 3(d).

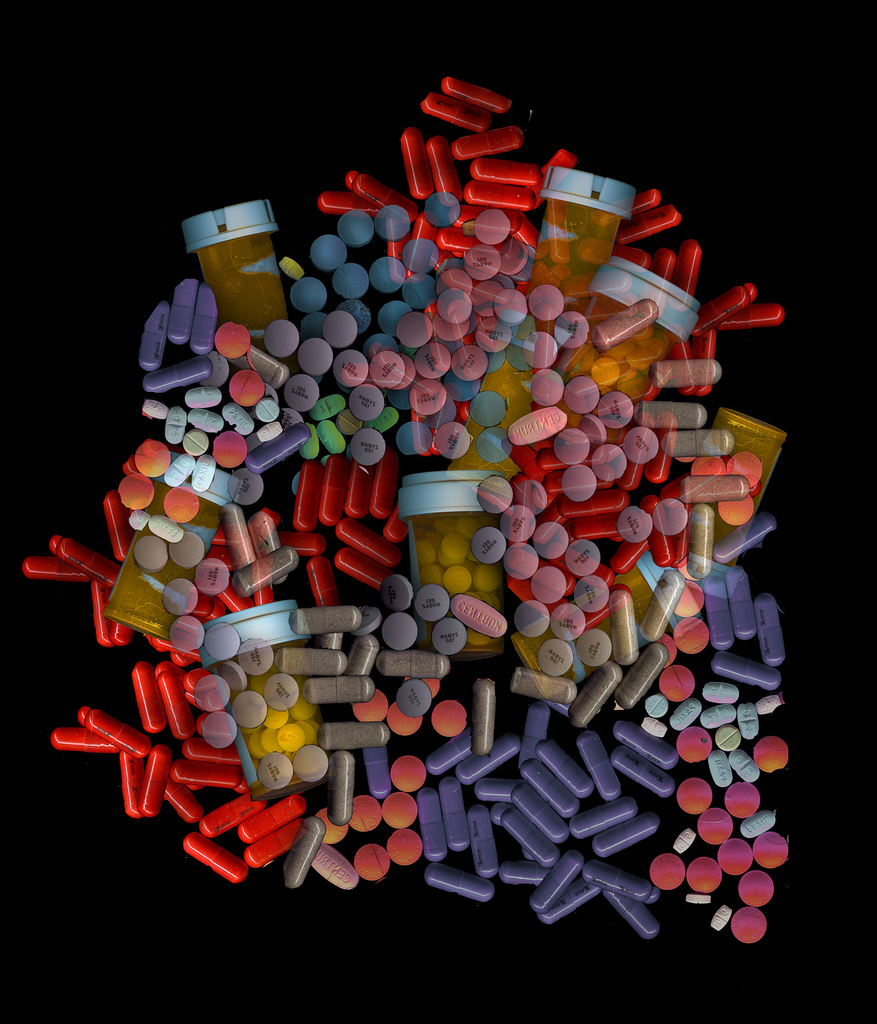

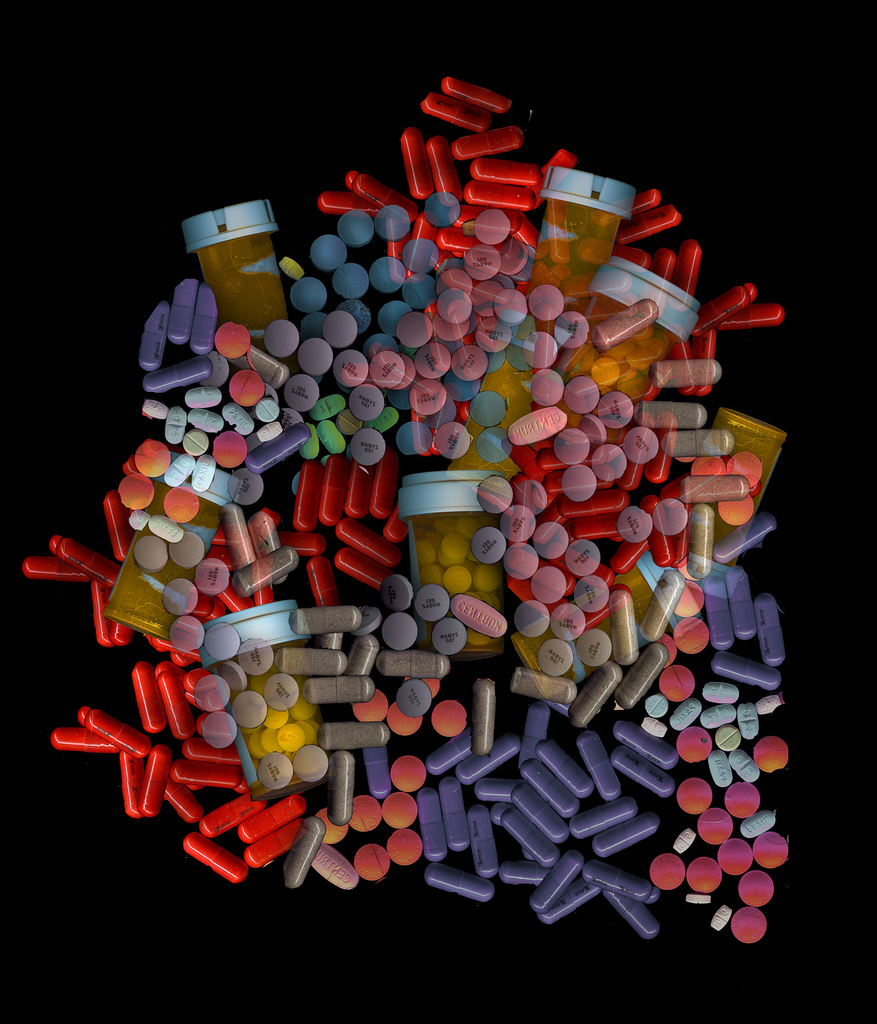

At the root of the case is Novartis’ Gleevec, a drug used to treat chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), a type of blood cancer. Novartis’ price for its version of the drug, Gleevec or Glivec, is INR 120,000 (USD 2400) per month, while generic versions are available for INR 8,000 (USD 160) to INR 12,000 (USD 240) per month.

Cancer Patients Aid Association procures the generic versions at discounted prices, and provides them to their members at subsidised rates. About 25% of the generic versions are provided free of cost to cancer patients.

Anand Grover, Senior Counsel and Director of Lawyers Collective HIV/AIDS Unit, who represented CPAA in this matter, says that the Supreme Court’s interpretation of section 3(d) keeps it intact. “It is alive and kicking. It gives life to Parliament’s intent of facilitating access to medicines and of incentivizing only genuine research.

“By refusing patent monopolies on minor changes to known molecules, this judgment will facilitate early entry of generic medicines into the market for other medicines and diseases too. The impact will be felt not only in India, but also across the developing world.”

In the past, Section 3(d) was also used as one of the grounds to disallow patents for minor modifications of several antiretroviral (ARV) medicines used to treat people living with HIV.

The Delhi Network of Positive People (DNP+)  had been filing oppositions to patent applications on ARV medicines on the basis of section 3(d). “This is a crucial victory for people living with HIV and other diseases who can continue to rely on India for access to affordable treatment,†says Loon Gangte of DNP+.

The ruling will have significant benefit for many developing countries – as much as 98% of generic drugs that India manufactures are exported to other poor countries.

Leena Menghaney for Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), which relies on Indian-made generic drugs to treat AIDS and other diseases in Africa and many poor countries, says Novartis’s attacks on the elements of India’s patent law that protect public health have failed.

“The Supreme Court’s decision prevents companies from abusing the patent system to get secondary patents on existing medicines, to block price-busting generic competition on HIV and other essential medicines. This confirms that all patent offices in India have to use this interpretation and the law is now clear and must be strictly applied.â€

Novartis has fought this battle for more than a decade. In 1998, Novartis filed a patent application in India for a product patent on the beta-crystalline form of imatinib mesylate (imatinib mesylate). The basic molecule, imatinib, had been discovered in the early 1990s and therefore was not patentable in India. India had not joined the WTO club then.

In 2005, the Chennai Patent Office heard patent oppositions filed by CPAA, represented by Lawyers Collective HIV/AIDS Unit, and other Indian generic companies.

In 2006, the Patent Office rejected Novartis’ patent application on several grounds, including section 3(d). Novartis has been fighting this battle since.

In an expected reaction, Novartis says it will not invest on research and development in India, and will move its R&D facilities to “favourable destinations”.

The company will continue to introduce products in the country, but not invest in R&D here, Novartis India Vice-Chairman and Managing Director Ranjit Shahani told a media briefing in Mumbai.

Experts in pharmaceutical industry have expressed concerns over the implications of the decision. “The pharmaceutical industry is driven by innovation, and they need to be able to recover their cost of drug development,” said an industry observer in the United States.

“If cheaper alternatives are available in the market, major drug developers will struggle to recover money, and this will affect future drug development.”

It takes anywhere from $1 billion to $2 billion to develop a drug, and the complete process ranging from research to securing patent takes 12 to 15 years for one drug.

(With inputs from a media release by Lawyers Collective HIV/AIDS Unit and Cancer Patients AID Association)

Leave a Reply